Bled Dry: How India exploits health workers

The COVID-19 crisis has been punctuated by frequent protests from healthcare workers—most often nurses and ASHA workers—complaining about unacceptable working conditions, inadequate staffing, low salaries, long hours of work, lack of personal protective equipment and so on. Instead of obtaining any respite, they have faced threats of dismissal or disciplinary action. Other than people clapping for them, and military helicopters showering petals over hospitals at the government’s command, almost nothing has been done for health workers during the pandemic.

Faced with a chronic shortage of staff, state governments are looking at short-term measures to shore up the public health system. In May, the Maharashtra government asked Kerala to lend it some nurses for a few months. Tamil Nadu has hired additional nursing staff, as well as doctors, on six-month contracts; the nurses will be paid just Rs 14,000 a month. Many states and local governments are recruiting workers paid by the day to carry out community surveys. Anganwadi workers and ASHA workers have been roped in to perform many tasks.

Meanwhile, the centre’s emergency allocation of Rs 15,000 crore for healthcare is to be divided between 28 states and eight union territories, and spent over four years. This represents just 0.075 percent of the stimulus package to deal with the economic fallout of the pandemic; even after all these months, there is no clarity on how it will be spent. The government has announced that Rs 2,000 crore from the PM CARES fund has been set aside to manufacture ventilators, but what about the specialised workers needed to operate them and the money to pay their salaries?

The pandemic has, once again, exposed a broken health system. India has just 1.7 nurses—in both private and public employment—for every thousand people, against the World Health Organisation-mandated three. The vast majority of Indians lack access to affordable medical care; in per-capita health spending, India ranks among the lowest in the world. (Sri Lanka spends four times as much, and Thailand ten times.) State governments have passed ordinances to reserve beds for COVID-19 patients in private hospitals, but the failure to create robust regulatory systems ensures that people are either refused treatment or made to pay astronomical bills.

The system is broken, not just for patients, but the majority of workers—nurses, technicians, paramedics, sanitation staff and others—employed in it. The pandemic merely underscores the urgent necessity of reform. Yet, both public and political discourses remain silent about healthcare: this implies a widespread belief that we can manage the pandemic, and the challenges to come, without fundamental change. This fantasy is morally unacceptable and extremely dangerous; the sooner we set about changing it, the better.

The exploitation of health workers is rooted in India’s social prejudices, the systematic undermining of labour laws, the decay of public services and the persistent refusal to regulate private healthcare. All these failures have deep roots.

In 1943, the colonial government set up an official body, known as the Bhore committee, to make recommendations on healthcare. Its report was submitted in 1946, just before India became independent. The report defined health as a public good, and recommended a public healthcare system, but had nothing to say about the private sector. Nehru’s government, citing a lack of money, favoured a small public system, to be expanded incrementally. Meanwhile, private practitioners were given a free hand—demands for regulation to preserve standards and prevent exploitation evaporated in the face of lobbying by doctors.

The basic framework of labour regulation was also created during the late 1940s and 1950s. Factory workers became an increasingly organised and powerful political force around this time, demanding laws to protect their rights. Labour, like health, was a concurrent subject, with both central and state governments involved in framing laws. Despite campaigns by trade unions, few laws were enacted to regulate small industries or services: the standard argument was that they would become uncompetitive if forced to pay workers properly. Elected representatives questioned the very necessity of giving workers paid leave. They complained that labour laws would spoil “familial relationships” at workplaces; that idleness would induce mischief; that workers would not know what to do with so many holidays. The legislation that was eventually passed contained loopholes designed to make it ineffective.

The state also reserved extensive discretionary powers to grant exemptions and define key terms and provisions. For example, in 1947, the Madras Shops and Establishments Act was passed to regulate working hours and holidays: all nursing homes, hospitals and lawyers’ chambers in the province were included in its ambit. This met with strong opposition in the Madras Legislative Council. Several lawyers and doctors among its members expressed indignation that the “learned professions” should be thus treated. A year later, their offices and establishments were exempted. In the end, a combination of legal challenges and exemptions excluded the vast majority of workers in small industries and services from the very laws purportedly enacted to protect them.State policies on labour and healthcare have a reciprocal effect on each other. Globally, workers were at the heart of key debates on social welfare during the middle decades of the twentieth century. The Second World War promoted unionisation, for labour played a critical role in the war effort. In the United Kingdom, this led to the Beveridge Report of 1942, promising social security for everyone, and the creation of the National Health Service after the war ended. BR Ambedkar, as the labour minister on the viceroy’s Executive Council during the war, tried to invite William Beveridge to India to prepare a comparable report. However, when the terms of his proposed investigation were narrowed down to the factory workforce, Beveridge withdrew. Instead, the economist BP Adarkar was chosen to write a report that recommended a health-insurance scheme and dedicated hospitals for permanent workers in large factories—these comprised only a tiny fraction of the workforce. The possibility of universal healthcare was set aside, along with legal protection for workers in small industries.

After 1947, India failed to develop a legal framework to hold the vast majority of employers accountable for working conditions or workers’ rights. It also failed to provide essential services such as education and healthcare. Lack of money was cited as an excuse, but, even though revenues and finances improved in subsequent decades, the state’s approach showed no change.

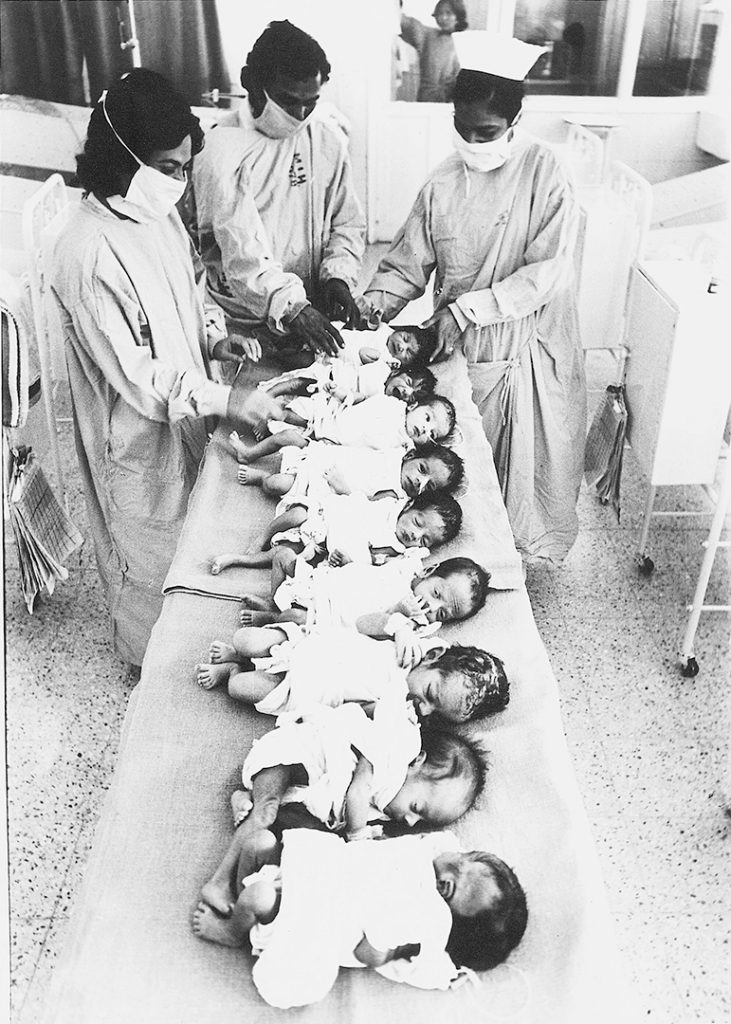

XAVIER GALIANA / AFP / GETTY IMAGES

Private healthcare expanded rapidly, beginning in the 1980s, with the encouragement of politicians and policymakers. It became corporatised, with the emergence of hospital chains such as Apollo. Private investment in medical education mushroomed. Multinational companies were granted licenses to manufacture drugs. Later, state governments set up insurance schemes allowing patients to obtain medical treatment in private hospitals. The sole, halting attempt to expand public healthcare occurred during the United Progressive Alliance’s first administration, between 2004 and 2009, when the National Rural Health Mission was set up at the urging of health networks on the margins of public discussion. Since 2014, the focus has shifted to more privatisation: the NITI Aayog is encouraging state governments to lease public hospitals to the private sector.

The state’s withdrawal from healthcare has gone hand in hand with its unwillingness to regulate the private sector. As many as 15 states have no legislation to register or regulate medical establishments. In 2010, the central government enacted the Clinical Establishments Act, prescribing registration and minimum standards for facilities and services (but saying nothing about working conditions or the wages of health workers). This law was energetically opposed by doctors’ associations, including the Medical Council of India, and has been adopted by only a handful of states.

Until the 1980s, the public sector provided secure employment, but without any mechanisms of accountability or transparency. The health system was marked by widespread corruption and poor standards of training and care. Later, contract-based work began to find favour. Most health workers nowadays are hired on temporary contracts. An increasing proportion of sanitation and paramedical staff are also sub-contracted. In addition, the National Rural Health Mission created a new category of “volunteer”—the Accredited Social Health Activist, or ASHA worker. In place of salaries, they are paid incentives based on official targets for institutional births and immunisation.

The private sector has always been marked by low pay and insecure contracts for most employees, except senior doctors and administrators. Between 2010 and 2011, nurses employed in private hospitals went on strike in several states. At the time, it was reported that their salaries—ranging from three thousand to six thousand rupees a month—were below the minimum wage. The strikes raised this somewhat although pay remains very low: roughly twelve thousand to fourteen thousand rupees a month for a trained nurse in Tamil Nadu (this applies to those employed in the private sector and contract nurses in the public sector), and much less for auxiliary and village health nurses on short-term contracts.

Training to become a nurse is rigorous, time-consuming and expensive. A three- or four-year course in a private institution costs between three lakh and five lakh rupees—88 percent of the country’s nursing institutes, producing 95 percent of all nurses, are privately owned. Most graduates accumulate large debts to pay for their education; confronted with bad working conditions, little respect, and low salaries, the dream of every nurse who cannot obtain a public-sector job is to go abroad.

Health workers face active hostility from the state, the courts and the public at large when they seek to improve wages or working conditions. State governments routinely deploy the Essential Services Act to prevent strikes. In November 2017, the Madras High Court ordered striking contract nurses employed by the state to return to work. The judges gratuitously advised them to give up their jobs if they felt they were being underpaid, for “the public” could not be made to suffer.

The notion of nursing as a calling or service is very common. These terms are rarely, if ever, applied to doctors. This reflects enduring divisions of gender, caste and class. Unpaid care work is overwhelmingly done by women and this association extends to jobs in health. Women dominate nursing—according to a WHO report, 83 percent of nurses in India are women. Their low earnings are a direct reflection of the view of care work as sewa, or service.

The notion of nursing as a calling or service is very common. These terms are rarely, if ever, applied to doctors.

Caste also plays an important role in determining the social and economic status of health workers. Members of the dominant castes usually avoid care work because of the social stigma attached to faeces, blood and death. A 2019 report from Oxfam India used data from the National Sample Survey to examine the caste composition of health workers. Of employees from dominant castes, 42 percent worked as doctors, 34 percent as technicians, and very few as nurses or cleaners. Among employees from the Other Backward Classes, 44 percent worked as technicians, 19 percent as doctors, and 6 percent as cleaners. Among Dalits, 41.5 percent were technicians and as many as 26 percent cleaners, with only three percent employed as doctors.

Historically, midwives in many parts of India hailed from Dalit castes. Although their skills protected lives, their work was considered polluting. They earned very little, and that mostly in kind. When missionaries set up the first training institutions for nurses, they struggled to find potential candidates. Nursing and midwifery were tied together in the public perception, and missionaries complained that no woman from “respectable” castes was willing to enter the profession. The first set of “native” nurses trained in the Madras Presidency in 1871 consisted of four Muslims and two Christians. Pregnant women from “respectable” castes avoided maternity hospitals because they feared to “lose caste.” Missionaries tried to work around this by training nurses who would help in home deliveries, but once again failed to get trainees from the “right” castes.

Nursing is less stigmatised nowadays, primarily because it offers an opportunity to emigrate to countries where there is greater respect and better pay. However, in India, it still remains a low-status job, badly paid and insecure. The situation of other health workers is even worse. As part of India’s vast informal sector—93 percent of the Indian workforce enjoys no legal rights—they are paid even lower wages, with even less security and hardly any benefits. Disdain for manual labour lies at the core of this denial of basic rights. Images of marching migrant workers and striking nurses have, if only for a moment, forced the middle class to acknowledge their essential contributions.

Over the years, many activists, union leaders and academics have suggested policies to improve workers’ rights and healthcare. Unfortunately, the two are rarely, if ever, examined in the same frame. The coming together of workers’ struggles and health campaigns might provide some momentum for change—especially if the middle class supported such a programme. But for that it will have to first recognise the value of a robust public health system. The failures of the private sector during the pandemic are quite clear.Respect for nurses, hospital attendants and sanitation workers is not something that comes naturally to members of the middle class, embedded in structures of caste and patriarchy. A childhood friend, trained at one of the best nursing institutions in Tamil Nadu, told me how a man being prepared for surgery once looked at her with pity, handed her a ten-rupee note, and remarked, “Poor thing, who knows who gave birth to you?” At the time, she was filled with shame for choosing a profession she considered noble, that would allow her to help others. In Europe, where she lives now, she encounters much more respect and gratitude for her work. If we cannot treat essential workers better, even in the midst of a pandemic, many others will follow the same path, leaving us just as vulnerable to the next crisis as we have been to this one.